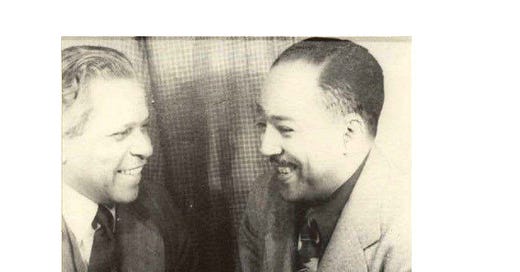

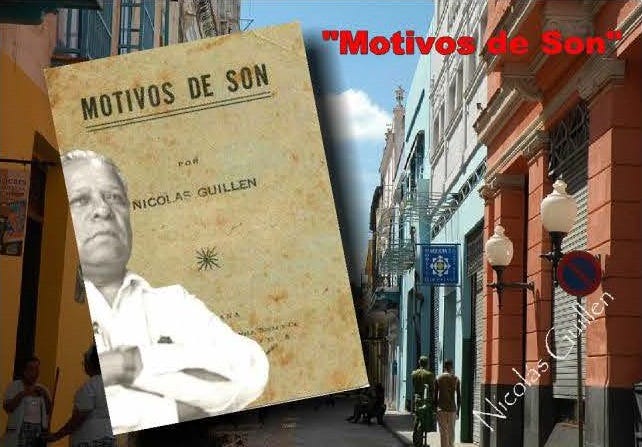

Public domain photo

Dear reader,

I’m going to take you back in time for a moment, a long way back, almost seventy years ago, when, as a teenager, I first fell under the spell of two Black poets: one, Langston Hughes, a North American; and the other, Nicolás Guillén, a Cuban. I hope this journey will briefly reveal for you the development of my own emerging weltanschauung (world view) and, more importantly, to serve as the backdrop for introducing and appraising the remarkable odyssey that brought these two activist negritude poets together.

The coincidence of these writers discovering each other at a moment in time when the infrastructure of electronic communication between peoples was limited to the telephone, is remarkable. Guillén and Hughes are versifiers whose careers were forged not only in the poetics and music of their own national circumstances, but in two linguistically and geographically disparate worlds. Guillén was from Cuba, a Spanish-speaking Caribbean island settled by Europeans more than 200 years before the Pilgrims landed in North America. It is a physical space about the size of Louisiana. Hughes, on the other hand, is from the half-a-continent-sized multi-lingual and ethnic melting pot that is the United States.

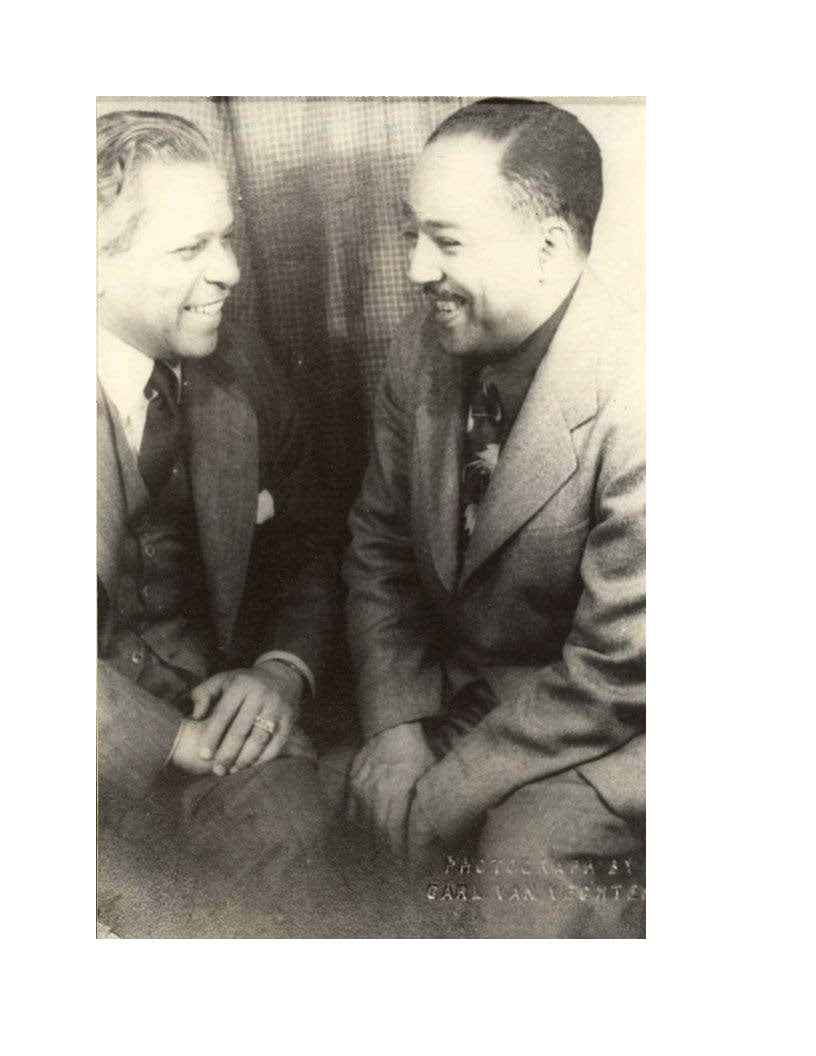

Photo courtesty of Alfred A. Knopf

The two men, one whose career was already established, Hughes; and the other, Guillén, whose career was about to takeoff, formed a personal and intellectual bond allowing both to create a radical, enduring poetic legacy, one of prolific symbiosis, during a highly productive decade of the 1930s.

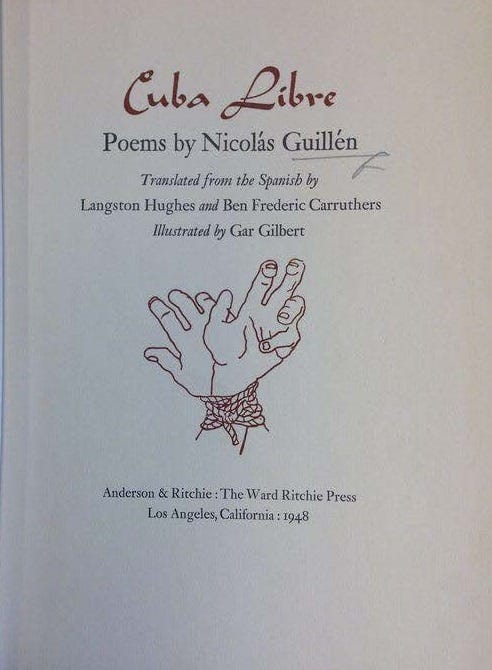

Theirs was a personal fellowship forged through a cross-cultural inventiveness which introduced to the world’s consciousness the poetic possibilities of joining musical rhythms to the written word. Both poets used musical signatures of their respective cultures. For Guillén it was the

Photo courtesy of The Ward Ritchie Press

son; and for Hughes, the blues. These allowed each poet to express unique perspectives about the complex social realities of Black folk in their societies. Guillén and Hughes wrote to elevate Black culture and Black cultural attributes; and to outspokenly express shared beliefs and themes related to societal exclusion based on blackness, language, and economic status.

Guillén and Hughes became critical influencers in the development of my own social conscience and aesthetics. I came of age in post-World War II Newark, New Jersey, in a household and a community where to speak well was as important as being physically self-reliant. In my 1950s neighborhood, verbal prowess and physical prowess went hand-in-hand so that a young man like myself could earn admiration, respect, and status.

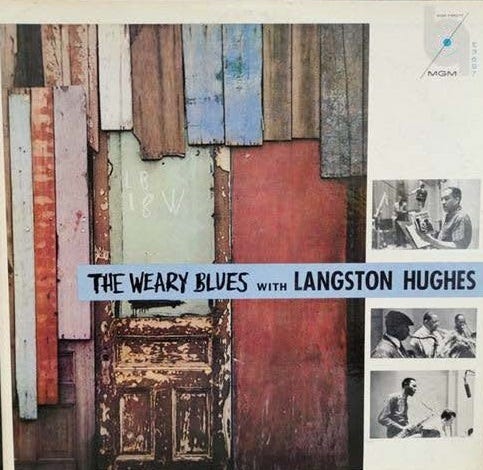

Photos courtesy of Public domain

Langston Hughes’ poetry came to my consciousness first, and almost twenty years later the versifying of Nicolás Guillénprovided me with the models of expressiveness and sources of language flow in my search for identity. Princeton footballer tailback Dick Kazmaier, Cuban welterweight boxer Kid Gavilán, and my own high school classmate Danny Enzer taught me lessons about physical toughness and dexterity.

Photo courtesy of Weequahic High School

In my teenage high school high school football life as the starting tailback in a single wing formation, when I took the snap from the center, I was always looking to emulate my tailback hero Dick Kazmaier of Princeton. Believe it or not, Langston Hughes was as important a figure to me as was Kazmaier. Hughes became the eruptive intellectual locus of the birth of what my early teenage self thought of as “my cool”; though I admit I did not fully understand the politics and social criticisms of the poet’s verses, nor was I as cool as I thought myself to be.

Photo courtesty of Public Domain

My parents had introduced the poetry of Hughes into our home. My mom worked her entire married life at the Newark Museum in Newark, New Jersey. There she moved easily in the world of her colleagues--painters, sculptors, jazz afficionados, art critics, and art acquisition specialists. My dad, who had started his adult work career as a writer for the now long-defunct Brooklyn Eagle could not make a living as a journalist and moved into commercial real estate; however much like my mom, he was a political and cultural progressive--a dreamer, a romantic, an insatiable reader and a committed member of the forward-thinking Jack London Society where he met my mom.

Photo courtesy of Bratter family

I still remember that as an young teenager, almost every month at my home in Newark, my Mom’s museum friends would gather to listen to jazz, recite poetry, dance, drink, and talk and talk. At that moment in time such a gathering of mixed race, multi-lingual, progressives was unusual. My parents allowed me to occasionally sit on the second floor steps and watch and listen.

Knowing that I was already interested in poetry, especially the Beats and Langston Hughes, one evening my parents encouraged me to recite a poem to the gathering. It turns out that one of my high school English teachers was the aunt of the iconic Beat poet Newark-born Alan Ginsburg. She not only introduced our class to sections of Ginsburg’s then blasphemous poem “Howl”, but to the poetry of Hughes via his “Weary Blues” and also to his collection of humorous prose writings in the self-deprecating “Simple” series of short stories.

I did not read the poems from any of his poetry books in the house that evening. Instead, I adventurously chose three short Hughes’ poems that I had already memorized. To this day, seven decades later, I still remember those poems. Imagine teenage me, if you can, standing in front of a group of fortyish sophisticated, highly literate and educated men and women -- the men attired in one-button roll jackets or jacketless, wearing turtle neck shirts, slim-legged pants and two-toned shoes; and the women, some wearing puffy blouses and voluminous skirts and others daringly wearing pants.

They were all seated in the people-close space that was our living room. They, a dozen or so, were squeezed together on the single couch or in chairs that had been pulled together to make their conversation more intimate. Their animated exchanges and musical syncopated laughter slowed to an adagio drawl as my dad humorously and grandiloquently introduced me, stating that I was known from coast to coast--that is, from the east coast of Newark’s Passaic River to the west coast banks of the same body of water.

Wearing blue jeans with big cuffs and a white shirt, I stood under the arch between the front entrance hallway facing the living room and where my parents’ crowd was seated and began reciting in what I imagined was my best Café Wha-inflected Greenwich Village coffee house rhythmic voice intoning in a slow cadence:

“I play it cool

And dig all jive

That’s the reason

I stay alive.

My motto,

As I live and learn,

is:

Dig And Be Dug In Return.”

Smiles and enthusiastic clapping followed as I confidently glided into:

“Folks, I'm telling you,

birthing is hard

and dying is mean-

so get yourself

a little loving

in between.”

More applause and laughter and feeling that I was genuinely channeling Langston Hughes, I finished my performance breathlessly concluding with these almost sacred verses which had only recently captivated me .

“Hold fast to dreams,

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird,

That cannot fly.”

I took a comical bow, turned and headed up the stairs to bed. There would be no looking back for me now -- words plus ball carrying; poetry as fists and fists as poetic justice for those who would cross me. Hughes would follow me all through my formative years. Later, already armed with the poetry of Hughes, I would find Guillén, though not at home nor in my neighborhood, but in the precincts of my undergrad Spanish Lit classes and conversations with my Profs. Each of the poets, Hughes first and then Guillén, would poetically remind me and the world that they and their people were not going anywhere:

STILL HERE

“I been scarred and battered.

My hopes the wind done scattered.

Snow has friz me,

Sun has baked me,

Looks like between 'em they done

Tried to make me

Stop laughin', stop lovin', stop livin'--

But I don't care!

I'm still here!”

And Guillén too would proclaim

“People, we’re still here

Under the sun

Our sweaty skin will reflect wet faces

Of the defeated,

And at night, while the stars burn at the top

Of our flames,

Our laughter will rise early over the rivers and the birds.”